When students learn new information, they need a hook to hang it on. Background knowledge is that hook.

Having the right background knowledge is critical to ensuring that students understand a lesson. This knowledge provides a foundation on which the rest of the lesson can be built. For ELLs, it can make a significant difference in their comprehension of the lesson and any related materials or texts.

When thinking about background knowledge and ELLs, it's helpful to think of two areas:

- Accessing students' existing knowledge

- Building new knowledge

Finding out what your students know about a particular topic can help you figure out how to make meaningful connections to their experiences, which is an important step in making your instruction more culturally responsive. This can also help you be strategic about which background knowledge to provide.

Here's a step-by-step process to help you think through important considerations for ELLs when looking at the background knowledge needed for your lessons.

Recommended reading

To see more research about the academic and cognitive benefits of culturally responsive instruction, see Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain by Zaretta Hammond.

1. Identify key background knowledge needed for the lesson

Review your lesson plan and:

- Look for key concepts, events, and references that students will need to understand the lesson

- Take a second look for areas that you may be taking for granted, such as names of places, daily activities that may vary across countries, cultural customs, and events from pop culture, etc.

- Identify vocabulary needed to comprehend the content

- Determine what background knowledge is most critical for students to understand the lesson

Video: An overview of background knowledge and ELLs

ELL teacher Amber Prentice discusses the necessity of accessing and building students' background knowledge before a lesson begins.

2. Identify students' existing background knowledge

Find out what background knowledge your students have on your lesson plan's topic. You can do this by:

- Asking students to speak with peers in their home language about a topic and report back in English

- Asking students to share what they know through drawing or writing in their home language

- Using a graphic organizer, such as a K-W-L chart.

- Using a See-Think-Wonder strategy, which uses a visual as a prompt to introduce a new topic

- Using a Concept Map to capture what students know and the connections they see between key topics

Inviting students to write their own questions about a topic

Note: Choose strategies that match your students' language and literacy levels. For example, having students speak in groups may be a good fit for younger students who aren't writing yet or for older students with interrupted formal education who are still developing literacy skills. Graphic organizers are helpful to use with younger students who have some language background or older students who are acquiring new language skills.

During this process, keep in mind that:

- ELLs bring a wealth of knowledge and experience to their classrooms.

- ELLs' background knowledge varies greatly from one student to another.

- ELLs' background knowledge will likely differ from students who were raised in U.S., and that students' background knowledge will vary by U.S. regions too. (For example, not all students live in climates where it snows in the winter.)

By getting individual student input, you will have a better idea of what students know about a topic. Then you can look for ways to connect the content to things that are familiar, students' experiences, and their funds of knowledge.

For many more ideas on accessing and activating students' background knowledge, see How to Connect ELLs' Background Knowledge to Content.

Note: ELLs may bring different perspectives or frames of reference to the topics you are discussing, such as in the example at the end of the article about how many continents there are. It's important not to frame background knowledge as a question of what's "right" or "wrong," but to approach these teachable moments with an open mind and encourage all of your students to do the same.

Video: Story setup: Pre-reading strategies for comprehension

Buffalo teacher Michelle Lawrence Biggar shares pre-reading strategies that will help lay the groundwork for ELLs before tackling a new text. Strategies include previewing vocabulary, activating background knowledge, and introducing academic concepts (such as literary elements) important to the text in an ELL-friendly way.

3. Build background knowledge students need

Once you have identified some areas of background knowledge your students need, build that knowledge by:

- Using visuals, realia, and multimedia resources and relating material to students' lives when possible.

- Pre-teaching important vocabulary words and concepts

- Explaining concepts and labeling them in English and their home language. This is a great time to point out cognates, or words that are related in multiple languages. For example, "This is the Statue of Liberty. Liberty means freedom. Liberty means libertad. The people of France gave us the Statue of Liberty…"

Home language connection

You can also use resources in students' home languages, such as books or videos. If you work with bilingual colleagues, such as teachers, paraprofessionals, or family liaisons, ask them if they have any recommended resources. And if you don't have any bilingual support available, considering connecting with a PLC online to find more resources. Other ELL educators around the country have a wealth of knowledge to share, particularly around low-incidence languages where there might not be as much material.

In addition, students can discuss, brainstorm, and write in their home language to show what they know and identify their key questions.

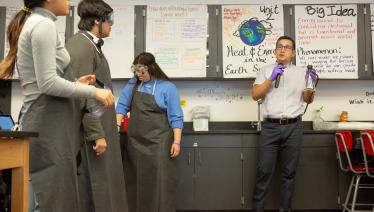

Video: Pre-teaching concepts and vocabulary before a lesson

ESOL specialist Katy Padilla collaborates with a fifth-grade team to plan a science lesson about vascular plants. You can also hear more about the planning process from Katy's related reflection interview.

Video: Teaching ELLs the names of all 50 states

ELL teacher Amber Prentice explains how she teaches ELLs the names of all 50 states in her middle school geography lesson.

4. Target the necessary background knowledge needed for comprehension

When reading grade-level text with ELLs, it's important to think carefully about which background knowledge (and how much) to provide.

- Build text-specific knowledge by providing students with information from the text beforehand, particularly if the text is conceptually difficult or has an abundance of information that is important. For example, if there are six main topics on the animal kingdom, highlight them beforehand.

- Establish the purpose for reading (e.g., "Now we are going to read to find out about a country called France. What are some things we might learn about France as we read?")

- Select a specific comprehension strategy for students to use.

- Look for books that students will find relatable. For more recommendations on selecting these books, see our related tips on using "mirror" books with students.

For more in-depth discussion of how much background knowledge to provide when reading grade-level texts, take a look at these blog posts from Dr. Diane Staehr Fenner, which discuss an American Educator article from Dr. Tim Shanahan on this topic:

5. Avoid assumptions

It is critical to avoid making assumptions about what background knowledge students do or don't have. Not only is this important for instruction, but it is critical for creating a welcoming classroom environment in which students feel respected.

For example, Dr. Ayanna Cooper shares a story in the video below about U.S. history teachers who mistakenly thought their Haitian student was an African American student who had a deep knowledge base about U.S. history. As mentioned above, the better you know your students, the better you can plan lessons that will give all students access to grade-level content.

Videos: ELL educators speak about background knowledge

Recommended Resources

- Unlocking English Learners' Potential: Strategies for Making Content Accessible

- Determining Which Background Knowledge to Teach ELs (Unlocking ELs' Potential)

- Flowchart for Determining Which Background Knowledge to Teach ELs (Unlocking ELs' Potential)

- Start with What They Know: Building Background Knowledge (Empowering ELLs)