An important first step in helping English language learners (ELLs) succeed is making them feel welcome in the classroom.

This will:

- increase their confidence

- make them feel more comfortable in the class

- build a foundation for positive relationships with you and their peers.

Here's how you can get started!

Stages of Cultural Accommodation

Use these ideas in PD!

Use these ideas in PD!

ESOL specialist Becky Corr shares ideas on how to use these strategies for professional development in this video.

The ELL student population includes students who were born in the U.S. and students who have immigrated from another country. For ELLs who have recently arrived in the U.S., they will face the challenge of learning a new language in addition to adjusting to an unfamiliar cultural setting and school system.

On a daily basis, ELLs are adjusting to new ways of saying and doing things. As their teacher, you are an important bridge to this unknown culture and school system.

In the same way that ELLs go through stages of English language learning, they may also pass through stages of cultural accommodation. These stages, however, may be less defined and more difficult to notice. Being aware of these stages may help you to better understand "unusual" actions and reactions that may just be part of adjusting to a new culture.

- Euphoria: ELLs may experience an initial period of excitement about their new surroundings.

- Culture shock: ELLs may then experience anger, hostility, frustration, homesickness, or resentment towards the new culture.

- Acceptance: ELLs may gradually accept their different surroundings.

- Assimilation/adaptation: ELLs may embrace and adapt to their surroundings and their "new" culture.

Moving to a new country and leaving a familiar life, relatives, friends, and language behind can be traumatic for children in the best of circumstances. Those challenges are compounded if children have experienced trauma, violence, or upheaval. Learn more about how culture shock can impact students in the classroom and affect student behavior so that you recognize signs if newcomers act out.

- How Culture Shock Affects ELLs (EverythingESL)

What is the 'silent period'?

It is also common for students who are learning a new language to be 'silent' for a period of time, when they are listening to the language around them without speaking yet (much as a young child listens to language first before learning to talk). This is considered the first stage of language acquisition.

Patience and creating opportunities for small successes in speaking with you and peers can help build students' confidence. In addition, keep in mind that students' silence could also be a sign of respect for you as an authority – and not a sign of their inability or refusal to participate.

Experience with trauma

Students may also have experienced trauma or face different kinds of hardship. You can better prepare yourself for this possibility by:

- taking some time to learn about some different ELL subgroups, such as refugees and unaccompanied children

- learning about students' experiences from colleagues such as family liaisons and ESL educators

- requesting training in trauma-informed practice.

Learn more from the following:

Videos: You Are Welcome Here

This award-winning documentary highlights how the Dearborn, MI public school district is helping its immigrant students succeed. Learn more about this project and see related videos.

Getting to Know Students

Learn how to pronounce students' names correctly

- Take the time to learn how to pronounce your ELLs' names correctly.

- Ask them to say their name.

- Listen carefully and repeat it until you know it.

- Model the correct pronunciation of ELLs' names to the class so that all students can say the correct pronunciation.

- Consider an activity in which students can share the meaning of their name, such as this Name Story activity or these related name activities.

Don't forget to smile and use positive body language!

A lot of communication happens through expressions, body language, and tone. Smiling and using positive body language can go a long way in making students feel welcome and comfortable, particularly if they are newcomers, as seen in the vignette shared by a teacher below.

Build relationships with students

Veteran teachers of ELLs always point to building relationships as the most important step in their work with ELLs. Not only does it increase engagement and support students' later academic success, it also provides invaluable information that can inform your instruction and family engagement.

In addition, it can help build bridges with students who may have particularly unique experiences, such as children in migrant farmwork families or Indigenous students.

See more ideas on how to build these relationships from the following:

- 8 Strategies for Building Relationships with ELLs in Any Learning Environment

- Getting to Know Your ELLs: Six Steps for Success

- Making Your First ELL Home Visit: A Guide for Classroom Teachers

- 10 Things You Need to Know About Your ELLs

Video: Showing students you care

Corpus Christi teacher Christine Price talks about the importance of showing students you care early on.

Identify students' strengths and interests

It's important to remember that ELLs bring lots of strengths, talents, and rich experiences to the classroom. Getting to know students' interests can help:

- build rapport

- engage students in learning

- find connections with new friends.

Families are also an important source of information and are often happy to talk about the activities that their child enjoys. They may also appreciate the fact that their child's teacher is taking an interest in the child's strengths and talents. (This is especially true in special education settings.)

Video: My students' many talents

Teacher Omar Salem describes a student who not only sings and dances but manages her own YouTube channel and edits all of the video she posts of her performances.

Video: Using parent letters to get to know my students

Albuquerque teacher Clara Gonzales-Espinoza asks her parents to write her a letter at the beginning of each school year telling her about the child's personality, interests, strengths, and anything else they think she should know. In this interview, Clara speaks more about this strategy and its impact on her relationships with parents and students.

Ensure that students have information about activities and clubs

Make sure that students have information about extra-curricular activities, sports, and clubs related to their interests. You can also encourage them to start their own club within the school.

ELL educator Christine Rowland notes, "Many students find involvement in school clubs and teams to be extremely helpful, as they are often experts in these areas, and they can provide a space where they more easily feel they belong."

Welcoming Students' Language and Culture

Invite students' cultures into the classroom

Encourage ELLs and their families to share their culture with you and your class. Show-and-tell is a good opportunity for ELLs to bring in something representative of their culture, if they wish.

Invite students and families to:

- share photographs, visuals, or meaningful artifacts such as flags or mementos

- tell a popular story or folktale using words, pictures, gestures, and movements

- share information about important holidays or celebrations.

Looking beyond the classroom

Imagine that you are walking into your school for the first time as a parent.

- What do you see on the walls?

- If your first language weren't English, would you see signs in your language?

- Would you see flags, maps, or books representing your home country?

- Would you see your child’s work on display in the hallway?

If you think more could be done to make families feel welcome, consider:

- sharing some ideas with colleagues or administrators and taking small steps that you can point to as successes

- looking for opportunities to celebrate all families and their languages, customs, and cultures, whether in the classroom or at a school-wide event

- keeping a lookout for a special part of their lives that other families might appreciate getting to know.

See more ideas in the following:

- Welcoming students' languages and cultures

- Welcoming students' celebrations and family traditions

- Making immigrant students and families feel welcome in school settings

- Engaging ELL Families: 20 Strategies for Success

Video: What happened when the students realized the Yemeni flag wasn't on stage

ELD Specialist Diana Alqadhi tells the story of some students who realized that the Yemeni flag was not featured prominently enough on stage before a school show.

Invite students' languages into the classroom

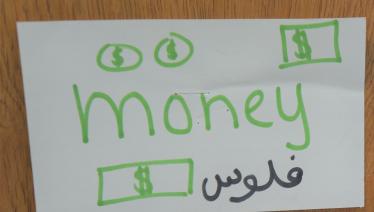

Label classroom objects to allow ELLs to better understand their immediate surroundings. These labels will also assist you when explaining or giving directions, and it gives peers an additional opportunity to learn some words in their classmates' language.

- Start with everyday items, such as "door/puerta," "book/libro," and "chair/silla."

- You may wish to ask students who can write in their first language or family members to help you with this project.

You can also invite students to teach the class some words from their home language.

Learn more about the resources available in students' home languages

Students benefit from support in their home language — what Dr. Fred Genesee calls their "most valuable resource." You may have access to learning material in students' languages, or you may be able to find resources that support those languages.

Language access for multilingual families

In addition, it's critical to understand what language access resources you have available through your school and district, particularly for communication with families. Keep in mind that all families have a legal right to information in their home language. Family liaisons, interpreters, ESL teachers, or administrators may have more information about what language access resources are available in your district.

Video: What Do School Districts Need to Know About Language Access?

This helpful overview about what language access means for school districts is a great introduction to the requirements, best practices, and funding streams related to language access in public education. This interview features Dr. Jennifer Love, the Supervisor of Language Access and Engagement in Prince George's County Public Schools, Maryland.

Video: Language Access for Multilingual Families

What does appropriate language access mean for multilingual families? This interview also features Dr. Jennifer Love.

Ensure your students see themselves reflected in the classroom

Ask yourself if students can see representations of their culture, race, gender, and other aspects of identity reflected in your:

- classroom materials and library

- lesson plans and activities

- classroom visuals (both in-person and virtual).

In addition:

- Look for ways incorporate books that represent your students' cultures across the curriculum and in your classroom library. Visit our recommended Books and Authors section for ideas.

- Learn more about culturally responsive instruction and tapping into students' funds of knowledge.

Success in the Classroom

Encourage your students

Some ELLs may not answer voluntarily in class or ask for your help even if they need it. ELLs may smile and nod, but this does not necessarily mean that they understand. Offer one-on-one support and encouragement as much as possible. For convenience, it may be helpful to seat ELLs near your desk.

Assign a buddy

Identify a classmate who will make a good buddy for new students — someone who is friendly, patient, and a good communicator to be a buddy. This student can make sure that the new student understands what he or she is supposed to do during class activities. It is helpful if the peer partner knows the ELL's first language, but not necessary. However, remember to never use another student as an interpreter in any situation.

Learn more about ways to increase peer interaction and collaboration in these related strategies.

Ask the class how they can help welcome new students

Ask students to brainstorm ways to help ELLs in particular. You may wish to make a list of ideas on how to welcome new students at the beginning of the year so that students have these strategies in mind if a student comes with little advance notice.

- Canadian students welcoming Syrian refugees (video)

- Sensitize Your Mainstream Students (Judie Haynes: everythingESL)

Be vigilant about health issues, dietary concerns, and allergies

Students may have specific health issues or dietary restrictions due to health, cultural, or religious reasons. Be sure that you learn all essential information you need to know about student health and diet from parents or guardians. For ELLs, be sure to confirm and clarify this information with the help of interpreters.

If you learn information about a student that would be helpful for other staff to know, particularly regarding health or food allergies, talk with administrators about how to keep the child safe. In addition, be sensitive to cultural or religious norms, such as fasting for religious reasons.

Creating a Shared Classroom Culture

Encourage students to take ownership of the classroom culture

Ask students to answer the following questions through drawings or written responses.

- How can I be a good classmate to others?

- What are examples of unkind or disrespectful behavior in the classroom?

To support ELLs in their discussions of these questions:

- Encourage students who speak the same language to discuss their ideas in groups.

- Provide scaffolded materials such as graphic organizers, sentence stems, and sentence frames.

- Use a picture book to talk about different kinds of behavior with students.

Create a shared set of classroom expectations together

- Return to your earlier discussion of what a respectful classroom looks like.

- Brainstorm ideas on possible class rules based on that discussion.

- Streamline the list of class guidelines or rules.

- Add any rules or guidelines that are missing.

- In order to establish appropriate consequences for disrespectful behavior, you may wish to come up with ideas with the class or determine those consequences yourself.

- Post the final list of classroom rules in the classroom.

- Translate the rules into ELLs’ native languages so that they can keep the list handy and share it at home.

To see an example of this process in action, take a look at ELL expert Carol Salva’s process for developing a community contract each year.

- Operation Respect: Activities for Safe and Respectful Classroom Community (Share My Lesson)

- Creating Classroom Rules with a Bill of Student Rights (Edutopia)

- Creating a Classroom Contract (Facing History)

- A New Set of Rules: Creating a “Class Constitution” (Learning for Justice)

- Speak Up at School: How to Respond to Everyday Bias, Prejudice, and Stereotypes (Learning for Justice)

Help your ELLs understand expectations for the classroom

ELLs may need some extra support in understanding expectations for classroom behavior. Helping them understand these expectations can avoid misunderstandings, discipline problems, and feelings of low self-esteem.

At the same time, it's important to remember that students bridging two cultures may need guidance on which behaviors are appropriate in which setting (such as eye contact, physical proximity, etc.). If you have questions, talk with a cultural liaison in the school to learn more about appropriate responses and ideas for helping students navigate a new culture. You can also learn more about cultural norms of your students, particularly related to schooling, to help inform your approach.

Here are a few strategies that you can use in class:

- Use visuals like pictures, symbols, and reward systems to communicate your expectations in a positive and direct manner.

- Physically model language to ELLs for classroom routines and instructional activities. ELLs will need to see you or their peers model behavior when you want them to sit down, walk to the bulletin board, work with a partner, copy a word, etc.

- Be consistent and fair with all students. Once ELLs clearly understand what is expected, hold them equally accountable for their behavior.

- Post a daily schedule. Even if ELLs do not yet understand all of the words that you speak, it is possible for them to understand the structure of each day. Whether through chalkboard art or images on Velcro, you can post the daily schedule each morning. By writing down times and having pictures next to words like lunch, wash hands, math, and field trip, ELLs can have a general sense of the upcoming day.

Finally, remember ELLs can make unintentional "mistakes" as they are trying hard to adjust to a new cultural setting. They are constantly transferring what they know as acceptable behaviors from their own culture to the U.S. classroom and school. Be patient as ELLs learn English and adjust — and remember that you will learn a lot from this experience too!

Related Videos

Videos: How can we make ELLs feel welcome in our schools?

These videos highlight helpful examples and ideas from educators across the country.

What to Do First: Creating a Welcoming Environment

Learn about these important first steps from teacher Amber Jimenez that will help ELLs feel welcome and get them on the path to academic success. Strategies include creating a print-rich environment and connecting content to students' cultures and experiences.

Top Tips for a Strong Start in a Newcomer Classroom with Carol Salva

Related Resources

- Creating a Welcoming Environment for PreK-5 ELs by Judie Haynes (TESOL Blog)

- Welcoming Immigrant Students Into the Classroom (Edutopia)

- 7 Tips for Building Positive Relationships with English-Language Learners (Edutopia)

- 10 Tips for Teaching English-Language Learners (Edutopia)

- 18 Ways to Support Your English Learners by Valentina Gonzalez (MiddleWeb)

- How We Can Support Our Newcomer Students by Tan Huynh (Empowering ELLs)