Dr. Ayanna Cooper, Ed.D., is an independent consultant who specializes in professional development for ELL educators. She is currently serving a second term on TESOL's Professional Development Standing Committee and serves as TESOL's Black English Language Professional and Friends Forum leader.

In this interview with Colorín Colorado, Ayanna discusses strategies for culturally responsive teaching, highlights issues around Black ELLs on which she'd like to see more research, and talks about empathy in the classroom.

To read more from Ayanna, take a look at her articles and blog posts written for Colorín Colorado, as well as this article in Language Magazine. Ayanna has also been featured in Teachers of Color.

Interview

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in the city of Boston and have always been very comfortable with linguistically diverse people. I remember in middle school that some of my classmates would spend part of their day being instructed in French, their native language. They were from Haiti, and I now realize how beneficial that must have been for them. I also went to summer camps in the city where the majority of the students were Black and Latino. When I began teaching, I was naturally drawn to my students of color and linguistically diverse students and wanted them to be successful. I would speak to them in my very limited Spanish and try to communicate with their parents in Spanish. Embracing their culture and recognizing the similarities between their culture and mine came naturally to me.

How did you get interested in working with ELLs?

An ELL teacher unofficially recruited me to teach ELLs. She encouraged me for about a year to earn the endorsement to teach English to Speakers of Other Languages. My first experience with ELLs was in a PreK classroom where I had twenty students and the majority were Spanish speakers. I was very concerned with the expectations to have them meet and exceed standards that were written for monolingual English speakers. Thankfully I was able to do my best to provide a print-rich and language-based learning environment.

I also wrote and was awarded several grants to provide additional resources, such as bilingual books on tape, for my students to listen to at home. I relied on my high school Spanish like never before — "Lávese las manos con agua y jabón" ("Wash your hands with soap and water") was repeated daily in our class! Watching my students' language develop throughout the school year was very rewarding. It was quite a learning experience for me, and a turning point in my career. I knew I wanted to specialize in teaching ELLs and helping other teachers to do so.

What are some ways for teachers to build connections with ELLs from diverse backgrounds?

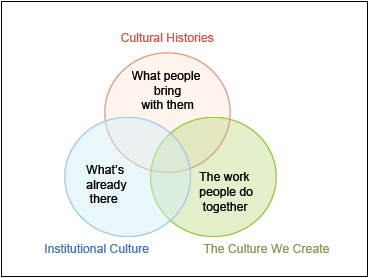

Even though it can be challenging, it's never too late to start trying, and you can begin right in your building — you don't need to travel abroad to learn about your ELLs! I suggest teachers try to learn as much as they can about the communities they serve. Talking with adults and community leaders can help teachers learn about their students and dispel myths or stereotypes. For example, when teaching a training course last summer, I arranged a visit for program participants to a local refugee center. The teachers were able to visit the community center and talk with the directors in order to learn more about their own student population. They found this an extremely helpful assignment since the school district was serving a large number of immigrant and refugee students.

Another example of the importance of getting to know students is when teachers have asked me, "Where are all of these students coming from?" The answer I sometimes give, depending on the situation, is "from the hospitals," because the ELLs we had in those changing communities were born in the United States. Yet the overall impression of the educators in that community was that the ELLs were just arriving in this country. Taking the time to find out about our ELLs is the most important step we can take to eliminate bias and become culturally responsive educators that can respond to our student needs.

In addition, I think it's important to make sure that we have all of the information we need about our students so that we can best meet their needs. I remember seeing a teacher who thought that the Black ELLs were in the wrong room since she didn't know the students and hadn't realized they were Haitian-Creole speakers. It's critical to make sure that all school personnel are well-informed about students' backgrounds so that colleagues can communicate effectively about student needs.

What are your suggestions for increasing diversity of classroom materials in all classrooms?

Teachers can take inventory of their classroom materials to assure they are as culturally responsive as possible. That means that regardless of the majority population in the classrooms, it's important to have materials that represent various cultures in order to increase and acknowledge diversity across the curriculum. Teachers can work together with administrators, media specialists, guidance counselors, family liaisons and community organizations to assure that as many diverse resources as possible become part of the school community.

In terms of Black History, for example, this could include submitting a grant for library books focused on the accomplishments of Black Americans, Black Immigrants' experience, and Civil Rights History. In addition, states that have adopted Common Core State Standards will be strongly encouraged to include diverse selections of text, including African American literature. Taking inventory to assure you have resources to adequately teach these standards throughout the academic year is imperative, not just during Black History Month in February.

What would you say to educators who think they can't teach ELLs since they don't speak another language?

I often hear that an ELL teacher must be fluent in the languages of his/her students. Being able to speak an additional language or two is extremely beneficial, and being fully literate in additional languages is even more beneficial. And there are things that teachers can do, like learn a few key phrases in their students' languages in order to build confidence with ELLs and their families.

Yet I want to make sure that potential ELL educators are not discouraged from the field if they have not studied a foreign language. They can make a valuable contribution to their students by developing an in-depth knowledge of language systems, linguistics and second language acquisition.

The other question, then, is how can these courses become part of all teacher education programs regardless of one's major? With the increase of linguistically diverse students in public schools, we need ELL professionals of all language and cultural backgrounds, and as a field we need to value all levels of language proficiency.

How can schools increase access to dual-language programs for communities that may not have much experience with bilingual education?

Reaching out to parents about new school programming can be challenging if you don't know where to start. I would suggest reaching out to community organizations that support the community in which you teach. Faith-based organizations and community organizations that assist immigrant and refugee families are one avenue. Once you know what is offered (or not), you can begin to partner with these organizations or at least increase access to the parents of the students you serve.

Knowing about the parents' level of education, their schooling experiences, if they are literate in more than one language and what they would like for their children will help you to make decisions about school programs and experiences offered. For example, you may have a number of parents interested in a dual-language summer enrichment program for their children. Knowing what the parents may want for their children will help educators shape programs to meet and exceed everyone's expectations.

What are some areas that have interested you in your work around Black ELLs and immigrants?

I'm interested in issues that affect Black ELLs and immigrants, including students of Afro-Caribbean and African descent, in the long-term. I'd like to know more about their experiences in the public school systems, their involvement in extra curricular activities, opportunities afforded to them and what kinds of things they are involved in beyond high school, employment or higher education. I'd especially like to know more about creating more leadership opportunities for them, such as assuring that our students are not only aware of leadership opportunities but also having the support to follow through with applications. Are all ELLs actively involved with their school communities? If not, how can we help them have access to those areas of their school experience? Extra curricular clubs, athletics, performing arts and summer programs are areas in need of representatives from linguistically diverse backgrounds.

What kinds of research would you like to see that focuses on Black ELLs in the future?

I would like to see more research focused on teacher attitudes and perceptions of Black ELLs. How can we focus more on the construct of race, privilege and socio-economic status? I often refer to it as "the skin we are in." How people perceive us is strongly tied to how we look and their experiences with people who look like us. We have to address this as part of teacher education and across various research forums. How can we transform limited experiences with or deep-rooted misconceptions of Black people and people of Afro-Caribbean and African descent into the ability to embrace those students, communicate with their parents, and ultimately support them to be successful?

How has your identity played a part in your career as an ELL educator?

As an African American female, there are challenges that ELLs often face that resonate with me — but they are also part of my strengths as an ELL educator. I know what it's like to realize that less is expected of me or to feel excluded and misunderstood. Yet I have used those experiences to inform my work with students and make me a better educator and teacher trainer. I have also overcome many of those challenges through my connections with supportive colleagues.

No matter what challenges you face, I think that finding or building a network of professionals, whether they have similar backgrounds or interests, is imperative. For me it has been my colleagues both in and outside of the ELL field who have provided me with strong support. Through the BELPaF (Black English Language Professionals and Friends) Forum, for example, I have found a network of other professionals who have an interest in the welfare of English language learners who happen to be of African descent.

Mentorship is also very important and has been beneficial to me, and recently I have been lucky to work closely with Dr. Diane Staehr Fenner through our connection at TESOL. In addition, I think that recruiting and supporting other professionals of color is essential to maintaining and expanding the presence of diverse candidates for future leadership roles, which I wrote about in the Fall 2012 magazine of Teachers of Color.

Where would you start in order to attract more African American educators to the ELL field?

I am always interested in ways to increase the presence of Black Americans and continue to support those of us who have been called to this area of teaching and learning. As part of teacher recruitment, I believe a focus on diverse candidates is imperative in all areas of the curriculum so that students develop relationships with educators representing a wide variety of backgrounds and perspectives.

Given the increasing need for teachers with ELL training, there are a number of places that would be ideal for recruitment, the first being Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Although teacher education programs exist in HBCUs, very few offer a major or a minor in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. We need to increase these programs capacity to prepare their teacher candidates for linguistically diverse learners.

Another area of possible candidates could come from alternative teacher education programs. Introducing teacher candidates early on to the needs and benefits of teaching linguistically diverse learners is key, rather than waiting until they are placed in front of students and expected to know how to effectively teach both language and content. Lastly, assuring that diversity is respected and welcomed across various leadership organizations is essential. For example, local, state and regional affiliates and International TESOL, Inc. are great places to learn more about the TESOL profession and how one can become more involved, such as through community volunteerism!

In what ways do you see ELL education as a Civil Rights issue?

The rights of English language learners today grew out of the Civil Rights movement. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or national origin, and that legislation applies to ELLs as well. I see myself as an advocate for all students and I feel it is my responsibility to continue ensuring that our students have access to the opportunities that our Civil Rights leaders (including those working for equality for Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Women's Rights) marched, protested, negotiated, and were incarcerated to obtain.

For our ELLs, I think that means focusing on advocating for appropriate resources, well-prepared teachers, a high functioning learning environment, and welcoming school communities. I'm thankful for the sacrifices and tenacity of earlier generations to ensure that the rights of all Americans would be protected and respected, and I look forward to continuing that work on behalf of all students today.

Do you have a particular success story you'd like to share, either from a student or in your professional development work?

I readily look for opportunities to support English language learners in my professional development work. For example, while serving on the board of Georgia TESOL I proposed we have Student Board Member position specifically for an English learner who is a student in high school or college. The goal of that position is to attract future leaders by inviting to have a seat at the table and to mentor them. Fortunately, the board approved my proposal and we now have a college student serving in that capacity.

In addition, I serve on the Lesley University Alumni Council as the 1st Vice President. Lesley University has organized book drives in the past to support a local public school in need. This year, with my assistance, we will be sponsoring the James A. Caradonio New Citizen's Center, a school for English language learners with limited or interrupted formal education in Worcester, Massachusetts. I toured the school the year before and was very impressed with the high expectations the teachers had for their students and how dedicated the students were. My tenure on the alumni council has allowed me to bring attention to a population of students and their school community that may not have been recognized before. I feel fortunate to be able to assist communities of English learners and their teachers across state lines.

Finally, I recently completed co-teaching an online course for a group of Peace Corp teacher educators. The participants were from all over Africa. This was my first "international" teaching opportunity. I learned so much from them and realized how similar our challenges are. Learning from and sharing my experiences, resources, teaching practices and assessments with them confirmed for me the importance of the work we are doing for the lives of English language learners worldwide.

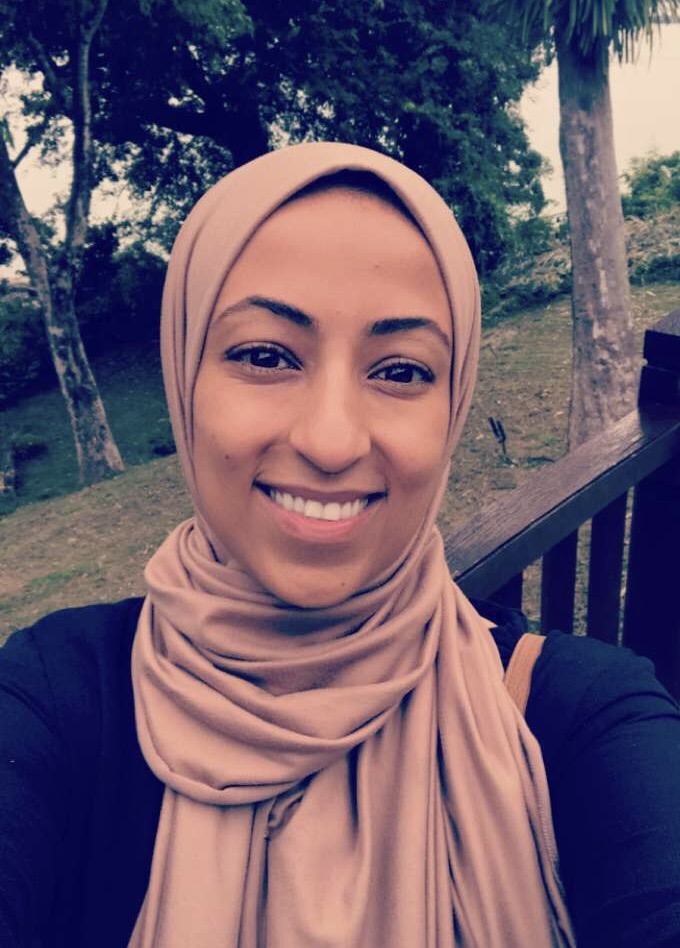

Nadra Shami currently serves as a Language and Literacy SIOP Trainer in Dearborn, MI. The daughter of immigrants, Nadra grew up in Dearborn and her first job was at the school she attended as a child. To learn more about Nadra’s work and the EL support offered in Dearborn, take a look at her interview as the

Nadra Shami currently serves as a Language and Literacy SIOP Trainer in Dearborn, MI. The daughter of immigrants, Nadra grew up in Dearborn and her first job was at the school she attended as a child. To learn more about Nadra’s work and the EL support offered in Dearborn, take a look at her interview as the

Dr. Tracey Flores and Dr. Sandra Osorio discuss the profound impact that Latinx books have had on them throughout their lives as students, parents, and educators. This article is part of our guide to

Dr. Tracey Flores and Dr. Sandra Osorio discuss the profound impact that Latinx books have had on them throughout their lives as students, parents, and educators. This article is part of our guide to